This September, Willamette Riverkeeper’s Co-Executive Directors navigated the length of the Willamette River, 194 miles in total, including 187 miles of mainstem and 7 miles of the Middle Fork above Springfield. For eleven days, through sun, rain, exhaustion, and awe, we carried not just ourselves, but the stories of this river and the people who depend on it.

From the headwaters to the Columbia River, we witnessed the Willamette in all its moods: dawn mist lifting over gravel bars, salmon leaping like stones skipping upstream, owls calling across the floodplain, and the flash of otters, minks, herons, and osprey reclaiming restored habitats. Each mile reminded us that the Willamette is not simply a river; it is a lifeline. It is memory, sustenance, recreation, resilience, and home to more than 70% of Oregonians.

Sit back, sip your coffee, and join us for a day-by-day behind the scenes look at our adventure down the Willamette River.

Day one: “The Wonder Launch”

WRK launched alongside community partners including Onward Eugene, American Rivers, Oregon Paddle Sports, Travel Lane County, and City of Eugene Recreation from Clearwater Park, above the confluence of the Coast and Middle Forks, at Glassbar Island, where we took this photo. The camaraderie and time together navigating the rapids in the upper Willamette fostered a strong sense of teamwork, reminding us that strong partnerships are the bedrock of lasting conservation.

Day 2: Osprey to Norwood

As we launched from Marshall Island, we were joined by Oregon State Parks rangers Steve Hernandez and Paul Williams, volunteers Mark Taratoot and Beth Shursun, WRK recreation staff members Luke Stuntz and Luke Weinstein, and documentary filmmaker Michael Sherman of Springfed Media. The crew visited Osprey Island, one of WRK's Water Trail properties, to install new water trail signage. These signs help paddlers identify places for safe, responsible river access from the river. Unfortunately, we also found a variety of garbage, including broken camp chairs, waterlogged cushions, disintegrated tarps, and fire rings, which we removed to dispose of as we were able.

Above: Oregon State Parks River Ranger Supervisor, Scott Youngblood, talks about Osprey Park and its value as part of the Willamette Water Trail system.

Below: At Norwood Island, WRK and friends set up camp for the evening after an "exciting" day, including a quick rescue involving one flipped canoe and some runaway camera gear! Norwood is an official Water Trail primitive camping area, accessible by watercraft only, and like most floodplain campsites, requires a "carry in, carry out" ethic for all gear, trash, and yes, poop too.

Day 3: Through corvallis and onto Tripp Island

On day three, we paddled through backchannels and floodplains, enjoying the relatively calm spirit of the river past Snagboat Bend and Peoria, with several dozen heron sightings. Heather and Michelle bid farewell to staff and volunteers in Corvallis and paddled downstream to Tripp Island. We embraced leftover nachos on the south end of the island from the main channel and fell asleep to jumping fish that sounded like boulders being thrown into the river.

Day 4: Tripp Island to LuCkiamute/Santiam Rivers

Oregon State Parks rangers joined Heather and Michelle from Tripp Island to Luckiamute Landing, an officially maintained Water Trail camping area. Accessed from the river only, this facility includes picnic tables, cleared tent space, and a portable restroom. This area is flanked by the confluences of both the Luckiamute and Santiam rivers, and is teeming with wildlife watching opportunities. Egret, red-tailed hawk, heron, river otters, and a variety of finned friends greeted us from dusk to dawn.

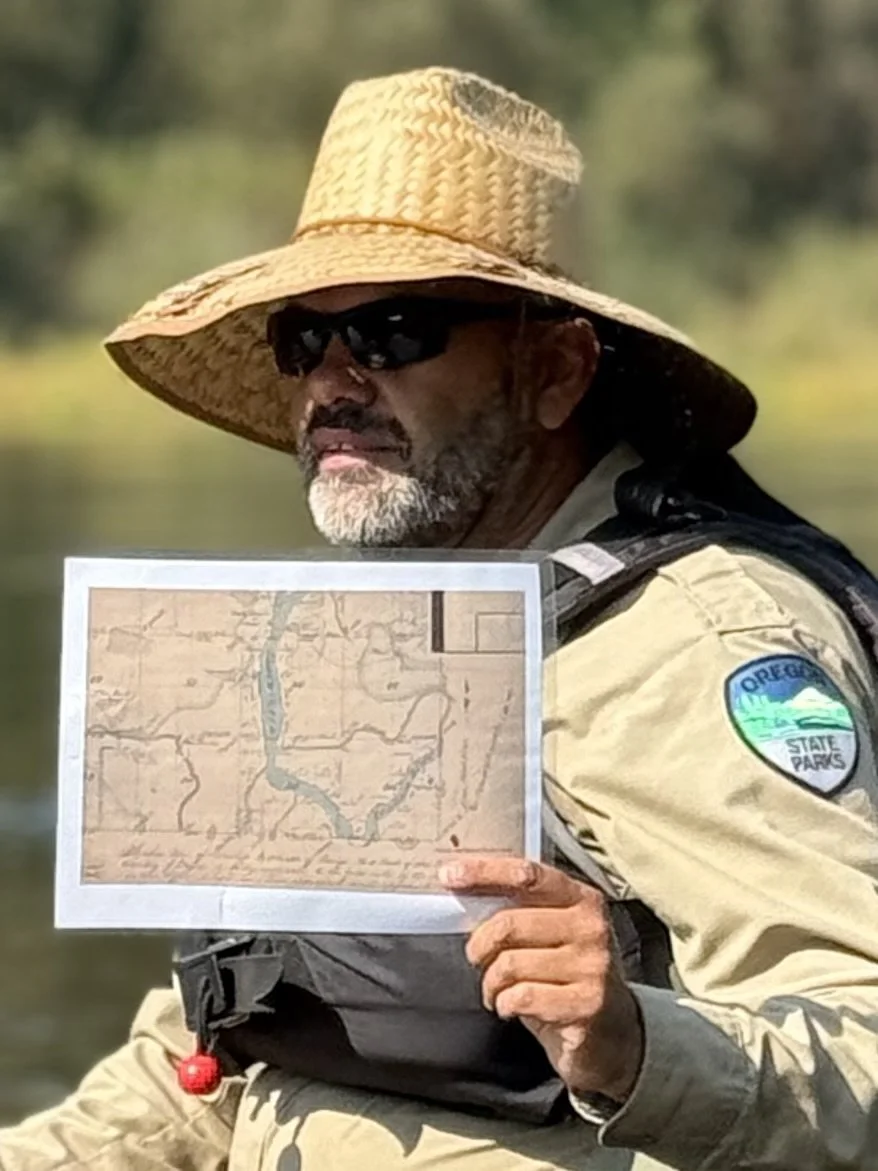

Steve Hernandez (also a WRK Board Member) holds up a map of the original Santiam River network.

Honoring the Kalapuya Peoples of the Willamette Valley

The Willamette River has long been central to the lifeways of the Kalapuya Peoples — including the Santiam and Luckiamute bands — who have lived, fished, and gathered along its banks for thousands of years. Their traditional ecological knowledge shaped the health of the Willamette Valley’s landscapes and waters long before statehood or settlement. Though their population was tragically reduced by disease and displacement in the 1800s, and their remaining members were forcibly relocated to the Grand Ronde Reservation under the Willamette Valley Treaty of 1855, their story is one of resilience. Today, descendants of the Kalapuya continue to revitalize language, traditions, and stewardship practices that honor their ancestral homelands.

Willamette Riverkeeper stands in respect and gratitude to the Kalapuya Peoples — past, present, and future — whose enduring connection to this river continues to guide our collective responsibility as caretakers of the Willamette. We hope you will take some time to hear more about this history by listening to the following interview with Michael Karnosh, Ceded Lands Manager of the Confederated Tribes of the Grand Ronde. Michael was available to greet Heather and Michelle as they landed at Luckiamute.

Day 5: Independence

A relatively short but enjoyable paddle after paddling past the Santiam, Heather and Michelle hit the halfway point for an overnight rest in the City of Independence, a vibrant hub for river recreation and small-town hospitality. Once a historic river port, it now welcomes paddlers, anglers, and cyclists to its lively riverfront park with a public boat ramp, amphitheater, and easy access to downtown dining and lodging. A Willamette Water Trail watercraft locker offers secure overnight storage for kayaks and canoes, making Independence an ideal stop for multi-day travelers. With scenic views, great food, and friendly amenities, it’s one of the best places to rest and recharge along the Willamette.

Located in Independence, this brewery offers a perfect riverside stop for paddlers and visitors alike. They serve craft beer, great food, and a welcoming atmosphere just steps from the Willamette River.

Based in Independence, this organization brings the community together on the water—offering year-round rowing programs that celebrate fitness, teamwork, and a shared love of the Willamette River. View the video below to learn more about their mission!

day 6: Salem and Keizer

After a comfortable night's rest at an AirBnB in Independence, Michelle joined the Salem Rowing Team for an early morning beginners' workout while tenured volunteer Eric Madsen helped collect and repack canoes for the journey downstream to Keizer.

Along the paddle to Salem, Michelle and Eric surveyed WRK's restoration project at Gail Achterman Wildlife Area, where WRK and the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife are reviving one of the Willamette’s most valuable floodplain forests. Through invasive species removal, native planting, and wetland enhancement, this 290-acre site is coming back to life. A powerful sign of success is the resurgence of wapato (Sagittaria latifolia)—a native aquatic plant with deep cultural and ecological roots in the Willamette Valley—marking the return of a healthier, more resilient river ecosystem.

In Salem, Eric and Michelle connected with the World Beat Dragon Boat Club. Members of the Angry Unicorns team met with us to discuss their mission of stewardship, accessible river recreation, and community health.

From Salem, Eric and Michelle paddled to Keizer to meet up with Heather and a local private land owner host. There, they toured a backchannel habitat restoration project and set up camp, welcomed by a fireside hamburger BBQ and the lull of a hammock at the water's edge.

Day 7: Mission State Park & Ash Island

No river trip could be complete without a day of rain, and the skies opened up in the wee hours of the morning, setting in motion a major downpour. Taking advantage of the pause, Heather and Michelle joined their host for breakfast, fueling up at the nearest restaurant with pancakes and eggs, waiting for the weather to break.

After the storm passed, the journey continued downstream to Willamette Mission with a group of students from the Willamette University Outdoor Program. They stopped at Willamette Mission State Park for a restoration tour with WRK's Restoration Manager, Vanessa Youngblood.

Willamette Riverkeeper’s restoration work at Willamette Mission has focused on reconnecting the river to its historic floodplain—removing invasive species, planting thousands of native trees and shrubs, and improving side channels to support salmon, lamprey, and other native fish. This effort has revitalized critical wetland and riparian habitats while improving flood resilience and water quality. Building on that success, our team is now working with partners to restore Oxbow Lake, a remnant channel just downstream, by enhancing hydrology, removing invasives, and reestablishing native vegetation. Together, these projects are bringing back the natural processes that sustain a healthier, more resilient Willamette River ecosystem.

Day 8: Newberg to Willamette Falls

After morning coffee and the remaining remnants of crackers and jerky, Heather and Michelle joined Michelle's father, John Emmons (who was running support for the trip all across the watershed), representatives of the Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde and indigenous filmmaker Kunu Bearchum of Morning Star Creative, for a meaningful river tour from Newberg to Willamette Falls aboard a beautiful pontoon boat generously provided by WRK volunteer, Bill Peterson.

Together, we explored the confluences of the Molalla and Pudding Rivers, toured Champoeg Park, where Indigenous-led restoration is bringing back native wild carrots (distinct from the invasive Queen Anne’s lace), and continued downstream through the Willamette Narrows, lands long home to the Kalapuya and Clackamas Peoples. This journey honored the deep cultural and ecological connections that continue to shape this stretch of river, reminding us that restoration is as much about healing relationships as it is about restoring habitat.

Above, Grand Ronde Tribal Elder, Greg Archeleta sits atop one of the many geological formations of the Willamette Narrows. Just upstream of West Linn and Oregon City, mark one of the most geologically dramatic stretches of the Willamette River. Formed thousands of years ago during the cataclysmic Missoula Floods, massive torrents of water scoured the basalt landscape, carving deep channels and leaving behind the rugged cliffs and rocky islands we see today. Over time, the river’s flow stabilized, creating a maze of narrow channels, eddies, and islands that now support rare plant communities, nesting bald eagles, and diverse aquatic life.

The Pudding River winds through the rich agricultural lands of the mid-Willamette Valley, draining a broad network of tributaries before joining the mainstem near Aurora. The slow-moving waters and seasonal wetlands of the Pudding River provide vital habitat for fish, birds, and wildlife, while reflecting both the beauty and challenges of balancing farming and river health in Oregon’s heartland.

Day 9: Willamette Narrows Close Up

After retiring to a real bed the night before, Heather, Michelle, WRK recreation and outreach staff member, Theresa Tran and lead mussel research scientist, Zee Seares Mazzacano intercepted Tualatin Riverkeepers (TRK), including executive director, Glenn Fee; program manager, Mark Fitzsimmons, and TRK board member, to coordinate a paddle from the Tualatin through the Willamette Narrows. Also joining were Tryon Creek Watershed Council executive director, Alexis Barton Castro; West Linn City Councilor, Mary Baumgardener, and a myriad of additional community volunteers.

The Tualatin River is a key tributary of the Willamette River — roughly 83 miles long — draining the fertile Tualatin Valley, supporting vital wildlife habitat and regional water supply before joining the Willamette near West Linn. In 2020, it was officially designated a National Water Trail by the U.S. Department of the Interior, making it one of only three such trails in Oregon for paddlers and river enthusiasts. The Tualatin River flows into the Willamette just upstream of the Willamette Narrows, where their confluence helps shape the dynamic channel system and rich ecological corridor that defines this dramatic stretch of the river.

Local watershed councils and the Tualatin Riverkeepers are vital partners for Willamette Riverkeeper because they extend the reach of river stewardship across the basin—connecting local communities to their tributaries, advancing clean water advocacy, and implementing on-the-ground restoration where it matters most. Together, these partnerships ensure that the health of the Willamette River is protected from headwaters to confluence, combining local knowledge, volunteer power, and shared commitment to a resilient, interconnected watershed.

Days 10-11: Clackamas River to Multnomah Channel

Ever closer to completing their journey, Heather and Michelle met up with WRK board president, Cathy Tortorici, and Kunu Bearchum, to put in with the WRK powerboat at Clackmette Park. Arriving in West Linn, we met with the Milwaukie River Stewards, including WRK volunteer and local artist, Susan Greenleaf (pictured below), better known around the area for her advocacy to clean up exposed styrofoam from aging docks, which releases harmful microplastics into the river system.

The Clackamas River delivers clean, cool water into the Willamette River at the confluence by Clackamette Park, strengthening flow, supporting salmon and steelhead runs, and improving water quality in the lower Willamette. Nearby, the headquarters for eNRG Kayaking (another important partner of WRK) takes advantage of this dynamic junction—where paddlers can easily explore downstream through the Willamette Narrows and into one of Oregon’s most scenic recreation corridors.

From there, the river widens and slows before entering the Multnomah Channel (at sunset, below), winding past islands, wetlands, and urban landscapes that serve as vital habitats and public access points. Yet, this reach faces growing challenges: recurring algae blooms near Ross Island Lagoon—fueled by warm, stagnant water and excess nutrients—pose health risks to people and wildlife alike.

Following our day’s journey and before settling into a houseboat on the Multnomah Channel before our final paddle to Kelly Point Park at the Columbia River confluence, Heather and Michelle, along with volunteers and partners from across the Willamette watershed, came together for the East Multnomah Soil & Water Conservation District's 75th Anniversary Celebration, where Heather spoke about EMSWCD's many faceted approach to improving the health of our Willamette River and its lower watershed communities.

Days 12: Superfund to the Columbia Confluence

Our final day paddling through the Portland Harbor Superfund reach began at Cathedral Park, where Heather and Michelle were joined by Theresa Tran, WRK’s Lower Willamette Recreation and Outreach Coordinator, along with several volunteers and community advocates engaged in CEI Hub policy work — including Nancy and Dean Hiser, David Labby, and Nikki Mandall. We were also joined by friends from the river’s headwaters in Oakridge, Leona Chiarappa and Holly Olson, eager to experience the downstream stretch of the watershed they help protect upstream.

Winding past massive ships, Sauvie Island, and several active restoration and mitigation sites, we passed the Critical Energy Infrastructure (CEI) Hub. We paused to reflect on its significance and the serious risks it poses to the river and surrounding communities. From the water, the concentration of fuel storage tanks and industrial facilities is striking—reminding us that this area sits atop unstable soils within an active seismic zone. Seeing it from the river underscored how vulnerable this corridor is to both pollution and disaster, and why stronger safeguards and long-term transition planning are essential to protect public health and the Willamette itself.

Paddling through the Portland Harbor Superfund Site is a journey through contrast—where the beauty of the Willamette River meets the weight of its industrial past. Towering cargo ships line the channel, a reminder of more than a century of manufacturing, shipping, and fuel storage that left behind toxic legacies of PCBs, heavy metals, and petroleum contamination embedded in river sediments. Yet amidst this history, signs of renewal are emerging. The EPA-led cleanup plan, now in its active phases, is driving sediment removal, capping, and long-term monitoring at dozens of sites along the lower river. Local partners, including Willamette Riverkeeper, continue to press for accountability and transparency while supporting habitat restoration and community engagement projects that reconnect people to these waters. From a kayak’s vantage point, the contrast is striking—steel hulls and cranes above, herons and osprey reclaiming the river below—a living testament to both the damage done and the ongoing work to heal one of Oregon’s most important waterways.